There is a kind of exhaustion that appears in midlife which does not behave like tiredness used to.

It does not resolve with sleep.

It does not disappear after a vacation.

And it often arrives at the very moment life appears stable, functional, even successful.

Career paths are established. Income is predictable. Family routines exist. The chaos of early adulthood has largely receded. From the outside, this phase of life looks settled — sometimes enviable.

Yet for many Americans over 40, exhaustion becomes a constant undertone. Not dramatic burnout. Not collapse. Just a persistent depletion that never fully lifts.

What makes this fatigue so unsettling is that it feels out of proportion to what’s visible. You can’t point to a single crisis and say, “That’s the reason.” The calendar looks normal. The responsibilities are familiar. The body seems fine on paper. And still, the mind feels crowded, the nervous system feels on-call, and recovery feels shallow—more like refueling just enough to keep going than truly replenishing. In midlife, energy isn’t only spent on tasks; it’s spent on holding life together: anticipating problems, managing people’s needs, absorbing uncertainty, and staying reliable.

This essay is not self-help. It is not motivational. It is an attempt to explain — carefully, rigorously, and honestly — why exhaustion intensifies in midlife, particularly in the United States, and why so many capable, responsible adults feel worn down even when nothing is “wrong.”

What many people are experiencing is not ordinary fatigue, but midlife exhaustion after 40 — a persistent state of depletion shaped by chronic stress, declining recoverability, and continuous cognitive load rather than by effort alone.

Key Takes:

- Midlife exhaustion isn’t a lack of effort or discipline: It’s what happens when responsibility, vigilance, and decision-making accumulate for decades while recovery capacity slowly declines.

- After 40, the problem is rarely energy — it’s recoverability: Chronic stress keeps the nervous system partially activated, making sleep and rest protective rather than restorative.

- Stability carries hidden weight: Career reliability, financial complexity, caregiving, and emotional availability converge in midlife, creating continuous cognitive load even when life looks “settled.”

- Exhaustion deepens when attention fragments: Constant interruptions and context-switching drain mental stamina, especially as cognitive recovery slows with age.

- This experience is amplified in the U.S.: Cultural expectations around productivity, self-reliance, and endurance make exhaustion feel like personal failure instead of a predictable outcome of long-term responsibility.

- What helps is not optimization, but regulation: Reducing cognitive load, increasing predictability, protecting deep attention, and restoring genuine psychological rest support recovery better than productivity tactics.

- Midlife exhaustion is not a problem to “fix.”: It is a condition to understand — one that requires clarity, not self-blame.

A Different Kind of Tiredness

Midlife exhaustion confuses people because it violates the rules they learned earlier in life.

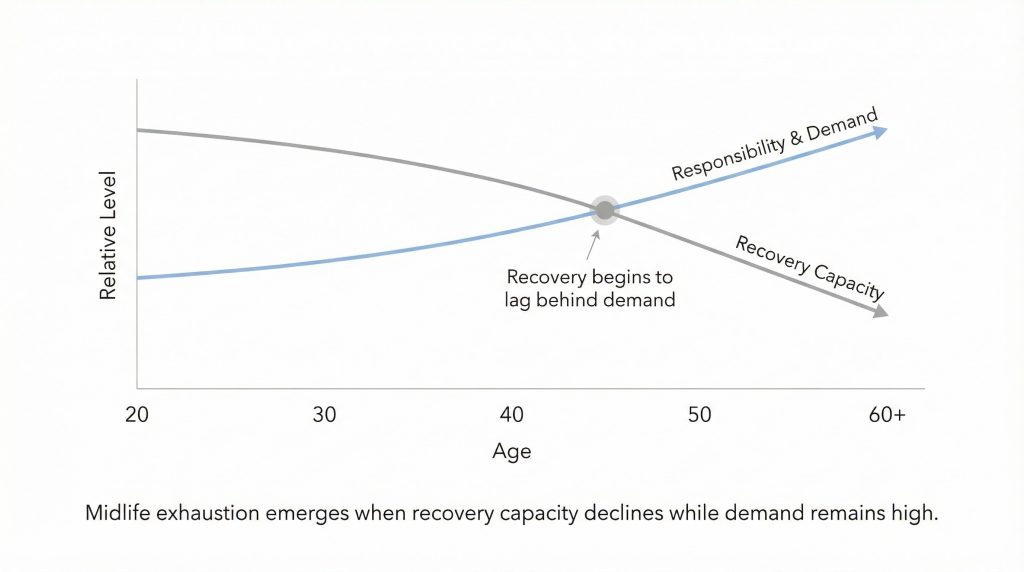

When you were younger, fatigue followed effort. You worked hard, you rested, you recovered. The relationship between cause and effect felt reliable. Energy was something you could spend and then regain. The body and mind reset themselves almost automatically, as long as you paused long enough.

After 40, that equation quietly breaks.

People begin to say things that don’t make sense to them:

“I’m sleeping.”

“I’m healthy.”

“My life is fine.”

“So why am I still tired?”

This question matters because it marks a transition. It signals a shift from acute fatigue, which is temporary and reversible, to something more diffuse and harder to name.

What many experience in midlife is chronic stress–related exhaustion — a state in which the body and mind remain functional, responsible, and outwardly capable, yet rarely experience full recovery. You keep showing up. You keep meeting expectations. But the sense of being restored never quite arrives. The system keeps running, but it no longer resets.

Unlike acute stress, which announces itself through clear events and endpoints, chronic stress accumulates quietly. It does not feel dramatic. It doesn’t arrive as a breakdown. It builds through years of responsibility, vigilance, obligation, and constant low-level decision-making. Each demand feels reasonable. Each role feels justified. But together they form a continuous background load.

What makes this especially difficult is that nothing feels overwhelming on any single day. There is no obvious emergency to blame. Instead, exhaustion emerges as a slow erosion — the result of carrying many small weights for a very long time without ever fully putting them down.

By midlife, many Americans are no longer sprinting.

They are not chasing chaos.

They are carrying — continuously, without pause — and the cost of that carrying finally becomes visible in the form of persistent, unrelieved tiredness.

What the Data Actually Shows (And Why It Matters)

This pattern is not anecdotal. It is measurable — and it appears consistently across health, psychology, and social research in the United States.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has documented rising reports of fatigue, stress-related symptoms, and emotional exhaustion among adults in midlife, even among those without chronic disease. This distinction is important. These are not populations experiencing acute medical crises. They are largely employed, insured, and socially functional — people who, by conventional standards, are “doing fine.” Yet their bodies and nervous systems report otherwise.

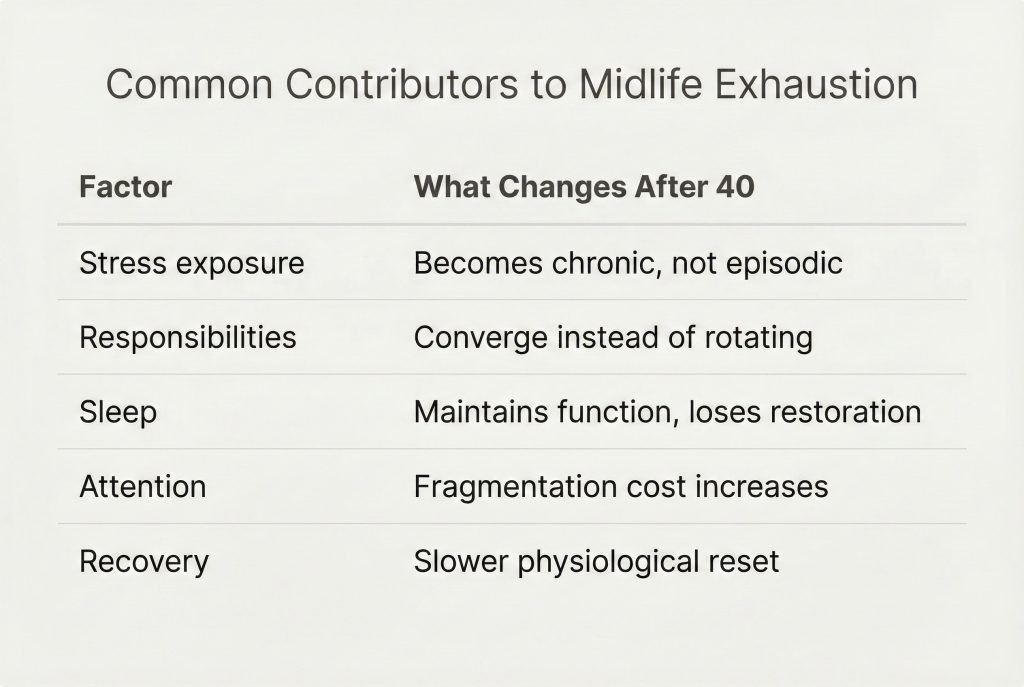

Similarly, the American Psychological Association has repeatedly found that stress does not naturally decline with age. Instead, stressors change shape. Caregiving responsibilities, financial complexity, and workplace expectations tend to stack rather than resolve, creating a long-term stress profile that is more continuous than episodic.

Perhaps most revealing is data from the Pew Research Center, which shows that life satisfaction follows a U-shaped curve: declining through middle age before rising later in life. This dip appears across income levels, education levels, and family structures. In other words, stability does not immunize people against strain.

This matters because it reframes exhaustion correctly.

Midlife fatigue is not primarily a failure of discipline, mindset, or gratitude. It is not evidence that people are doing life “wrong.” It is evidence of cumulative load — and of what happens when a human system is asked to operate at high reliability for decades with limited opportunities for true recovery.

Stability Isn’t Light — It’s Dense

Stability is often imagined as relief. In reality, stability often brings density.

Earlier in life, instability is obvious. You feel the chaos. You react to it. But in midlife, stability hides its weight behind routine. Life looks orderly, yet the number of moving parts quietly multiplies. What changes is not the presence of responsibility, but its concentration.

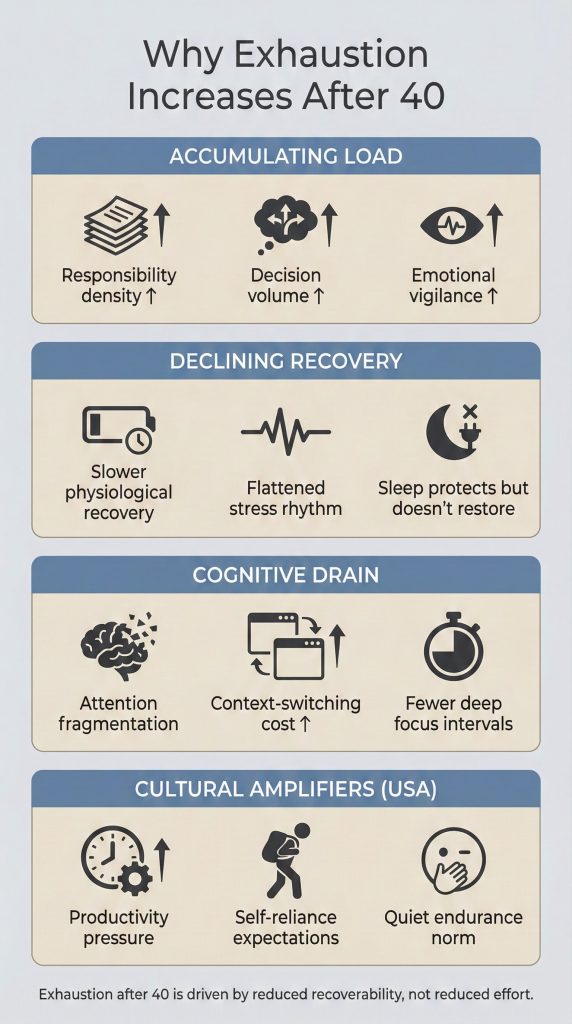

By midlife, responsibilities converge rather than resolve:

- Career accountability peaks, even if ambition plateaus. You may no longer be climbing, but you are expected to be reliable, competent, and available.

- Financial obligations expand. Mortgages, education costs, retirement planning, healthcare decisions—each one individually rational, collectively demanding constant attention.

- Aging parents begin to require emotional, logistical, or financial support, often unpredictably and without clear timelines.

- Children, though more independent, still require presence, guidance, and psychological availability at moments that cannot be scheduled.

Each responsibility is manageable in isolation. None of them feel unreasonable. Together, however, they create continuous cognitive demand—the ongoing mental effort required to keep multiple systems functioning smoothly and without failure.

This is where decision fatigue becomes central.

Decision fatigue is not about big, dramatic choices. It is about the accumulation of thousands of small, consequential decisions made every day: adjusting schedules, managing expectations, resolving low-level conflicts, anticipating problems before they surface, and ensuring that nothing quietly falls apart. Much of this work happens invisibly, inside the mind, without external recognition.

Unlike physical labor, cognitive and emotional management does not produce clear exhaustion signals. You don’t feel “worked out.” You feel vaguely depleted. The body remains upright. The calendar stays full. But the sense of internal surplus disappears.

There is no moment of collapse.

No clear line you cross.

There is just an absence of restoration.

Stability, in this sense, is not light. It is compressed responsibility—the sustained effort of holding many things together at once, over long periods of time, without ever fully setting them down.

The Physiology of Stress After 40

To understand why exhaustion deepens with age, physiology matters — not as an abstract concept, but as a lived biological reality.

Stress activates the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, releasing cortisol to mobilize energy, sharpen focus, and prepare the body for action. In short bursts, this system is adaptive. It helps you meet deadlines, respond to threats, and solve problems efficiently. When the challenge ends, cortisol levels fall, and the body returns to baseline.

Over long periods, however, this system changes.

Research synthesized through the National Institutes of Health shows that chronic stress can disrupt normal cortisol rhythms. Instead of rising and falling predictably across the day, cortisol levels may remain elevated or become blunted. In either case, the body’s ability to fully power down and recover is compromised. The stress response becomes less flexible — slower to deactivate, quicker to react.

This loss of flexibility is subtle, but consequential. It means the nervous system stays partially engaged even during rest. The body never quite receives the signal that it is safe to stand down.

After 40, this matters more.

As part of normal aging, physiological recovery capacity declines. Cellular repair slows. Sleep architecture changes. The margin for error narrows. When recovery slows while stress exposure remains constant — or increases — the result is persistent fatigue that feels disproportionate to daily effort.

Nothing dramatic is required to trigger this state. There may be no trauma, no illness, no acute crisis. The system simply spends too many years in “ready mode.”

This is why many midlife adults describe feeling “always on.”

Not anxious in an obvious way.

Not panicked.

Just unable to fully disengage.

They are not fighting emergencies.

They are not running from danger.

They are maintaining vigilance — monitoring responsibilities, anticipating problems, staying alert to what could go wrong. Biologically, vigilance is expensive. It consumes energy even when nothing happens.

Over time, the body adapts to this state by conserving resources. Energy feels lower not because effort has increased, but because recovery has quietly diminished. Exhaustion, in this context, is not a personal failing. It is the physiological cost of long-term alertness in a system that was never designed to stay activated indefinitely.

Why Sleep Stops Being Enough

One of the most unsettling aspects of midlife exhaustion is that sleep no longer feels restorative.

People do what they are supposed to do. They go to bed earlier. They protect their sleep schedule. They track their hours. And yet, they wake up feeling as if they never truly shut down. The expectation that “a good night’s sleep will fix it” quietly stops being true.

This is often misunderstood as a sleep problem. In many cases, it is not.

The issue is nervous system activation.

When stress becomes chronic, the body struggles to fully disengage, even during sleep. The brain may enter sleep stages, but the nervous system remains partially alert. Rumination, anticipatory stress, and background vigilance keep the system in a low-grade state of readiness. Biologically, the body is resting just enough to avoid breakdown, but not enough to replenish reserves.

In this state, sleep becomes protective rather than restorative. It prevents collapse, but it does not rebuild surplus energy. You wake up functional, not refreshed.

This is why vacations often disappoint. The first few days may bring relief, but the nervous system does not reset simply because the environment changes. The stress architecture — the learned pattern of constant alertness — travels with you. Within days or weeks of returning to routine, the familiar exhaustion reappears, often without any clear trigger.

What has changed is not the quality of sleep itself, but the depth of disengagement the body is capable of reaching. Midlife stress conditions the nervous system to stay on watch, even during rest. It learns that standing down completely is risky.

Rest, under these conditions, becomes maintenance rather than renewal. It keeps the system running, but it does not restore a sense of internal surplus. The body survives the day, but it does not truly recover from it — and that gap, repeated night after night, is where persistent midlife exhaustion takes root.

Attention Is Aging Faster Than We Are

Another major contributor to midlife exhaustion is attention fragmentation — a form of fatigue that accumulates quietly and is often misattributed to lack of motivation or aging itself.

Modern life demands continuous partial attention. Email, messaging platforms, notifications, news cycles, and constant low-level decision-making pull the mind in multiple directions throughout the day. Even when nothing feels urgent, the brain remains in a state of readiness, scanning for the next input. Over time, this erodes mental stamina in ways that are difficult to notice moment to moment.

For adults over 40, the cost of this fragmentation increases. Cognitive flexibility does change subtly with age. The brain remains capable, but context-switching requires more effort than it once did. Tasks that previously felt automatic now demand sustained concentration. Interruptions become more draining, not because ability has declined, but because recovery between attentional shifts is slower.

What makes this particularly exhausting is that fragmented attention rarely feels like “hard work.” There is no clear sense of exertion. Instead, energy is lost in small, repeated withdrawals — each interruption consuming a little more focus than it returns.

Exhaustion, in this sense, is not about working harder or longer.

It is about processing more interruptions with fewer uninterrupted mental intervals.

The mind spends more time reorienting itself than actually settling into depth. Over days and years, this pattern leaves people feeling mentally tired even on relatively light days. The work may not have increased, but the cost of maintaining focus has — and that cost becomes increasingly visible in midlife.

The Psychological Weight of Irreversibility

Midlife exhaustion is not only physiological or cognitive. It is existential.

After 40, decisions carry a different emotional weight. Paths feel narrower. Time feels less elastic. Mistakes feel harder to undo. Choices that once felt exploratory now feel defining, and that shift subtly alters how the mind processes everyday life.

This creates a background tension that rarely surfaces as conscious anxiety, but continuously taxes the mind: the stress of irreversibility. It is not panic. It is a low-level vigilance rooted in awareness — the understanding that time, energy, and opportunity are no longer infinitely replenishable.

Even when life is objectively stable, the awareness that certain doors are closing increases cognitive load. The mind works not only to manage the present, but to quietly measure what has been chosen against what has been left behind. This comparison rarely demands attention, yet it never fully disappears.

What makes this exhausting is that the evaluation is constant but unresolved. There is no decision to make, no problem to solve — only a continuous reckoning with finality. That quiet, unspoken accounting consumes energy, even when nothing is actively wrong, and adds a psychological weight that younger minds simply do not carry in the same way.

Why This Hits Americans Especially Hard

Culture amplifies physiology.

American identity places high value on productivity, self-reliance, and usefulness — particularly in midlife. This is the phase of life when individuals are expected to be dependable, competent, and emotionally steady. You are supposed to have figured things out. You are expected to carry others, not be carried.

Admitting exhaustion during this phase often feels inappropriate, even shameful. Fatigue is internalized as a personal shortcoming rather than understood as a predictable outcome of prolonged responsibility. People tell themselves they should be grateful, tougher, more disciplined. The question becomes not “Why am I exhausted?” but “Why can’t I handle this better?”

Healthcare anxiety compounds the issue. Insights highlighted by the Office of the U.S. Surgeon General recognize loneliness and chronic stress as significant public health concerns. Yet because exhaustion does not always present as illness, many adults hesitate to name it or seek support. It does not fit the cultural narrative of resilience or success.

The result is quiet endurance.

People keep functioning.

They meet expectations.

But recovery never fully happens.

In this context, exhaustion becomes invisible — not because it isn’t real, but because acknowledging it conflicts with deeply ingrained cultural expectations about what adulthood, competence, and strength are supposed to look like.

Loneliness Without Isolation

A paradox of midlife exhaustion is that it often exists alongside social connection.

Many adults over 40 are not isolated in the traditional sense. They interact daily with colleagues, family members, and communities. Their calendars are full. Their days are socially populated. Yet emotional availability quietly decreases. Conversations become transactional. Roles replace presence. Vulnerability begins to feel costly rather than relieving.

This creates a subtle form of loneliness — not the absence of people, but the absence of psychological rest. There are few spaces where one can speak without managing impressions, solving problems, or absorbing others’ needs. Even connection carries responsibility.

Without environments where the nervous system can fully stand down, recovery remains incomplete. Social life continues, but it no longer replenishes. Over time, this quiet depletion compounds exhaustion, not because support is missing, but because true emotional rest has become rare.

What Actually Helps

There are no quick fixes for chronic exhaustion. Research does not support simple solutions, and anyone promising rapid relief is likely addressing symptoms, not causes. However, several patterns consistently correlate with improved recovery:

- Reducing cognitive load, not just working fewer hours

- Longer uninterrupted attention blocks, rather than constant responsiveness

- Predictability, which lowers background stress

- Meaningful social connection, not performative interaction

What matters most is that these changes reduce baseline strain, not just visible effort. They allow the nervous system to spend more time in a state of safety rather than readiness.

These are not productivity techniques. They are stress-regulation strategies. Their purpose is not to increase output, but to restore the body’s ability to recover.

The goal is not to reclaim youthful energy.

It is to restore recoverability.

This framework is designed to be cited, not decorated.

What We Still Don’t Fully Understand

Despite growing research, significant questions remain — and those gaps matter.

Why do some individuals recover more easily under similar conditions, even when stress exposure looks nearly identical? How much of midlife exhaustion is driven by biology, and how much is shaped by culture, expectations, and learned patterns of self-demand? And what role does meaning play — not as motivation, but as a physiological signal that influences recovery and resilience?

These questions point to the limits of current models. Human exhaustion does not follow a single pathway. It emerges from the interaction of body, mind, context, and time. Two people can live outwardly similar lives and experience vastly different levels of fatigue.

Current research offers patterns, not certainty. Acknowledging these limits is not weakness; it is intellectual honesty. It reminds us that midlife exhaustion is not a problem to be “solved,” but a condition to be better understood — with humility, nuance, and respect for complexity.

A Final Thought for the Quietly Tired

Exhaustion after 40 is rarely a failure of discipline, gratitude, or resilience. It is not evidence that something has gone wrong internally, or that a person has fallen short of some invisible standard.

More often, it is the cost of long-term responsibility in a system that rarely pauses — a system that rewards reliability, endurance, and constant availability while offering few mechanisms for genuine recovery. Over time, carrying that weight leaves its mark.

Understanding this does not solve everything. It does not remove obligations or restore lost energy overnight. But it reframes the problem accurately. And sometimes, that reframing alone eases a burden that has been carried silently for years — replacing self-blame with understanding, and isolation with a quieter sense of recognition.